Falling inflation – what does it mean for investors

Key points

- Inflation is in retreat thanks to improved supply and cooling demand. A further fall is likely this year.

- Australian inflation remains relatively high – but this mainly reflects lags rather than a more inflation prone economy.

- Profit gouging or wages were not the cause of high inflation.

- The main risks relate to the conflict in the Middle East escalating and adding to supply costs; a surprise rebound in economic activity and sticky services inflation; and floods, the port dispute and poor productivity in Australia.

- Lower inflation should be positive for investors via lower interest rates, although this benefit may come with a lag.

- The world is now a bit more inflation prone so don’t expect a return to near zero interest rates anytime soon.

Introduction

The surge in inflation coming out of the pandemic and its subsequent fall has been the dominant driver of investment markets over the last two years – first depressing shares and bonds in 2022 and then enabling them to rebound. But what’s driving the fall, what are the risks and what does it mean for interest rates and investors? This article looks at the key issues.

Inflation is in retreat

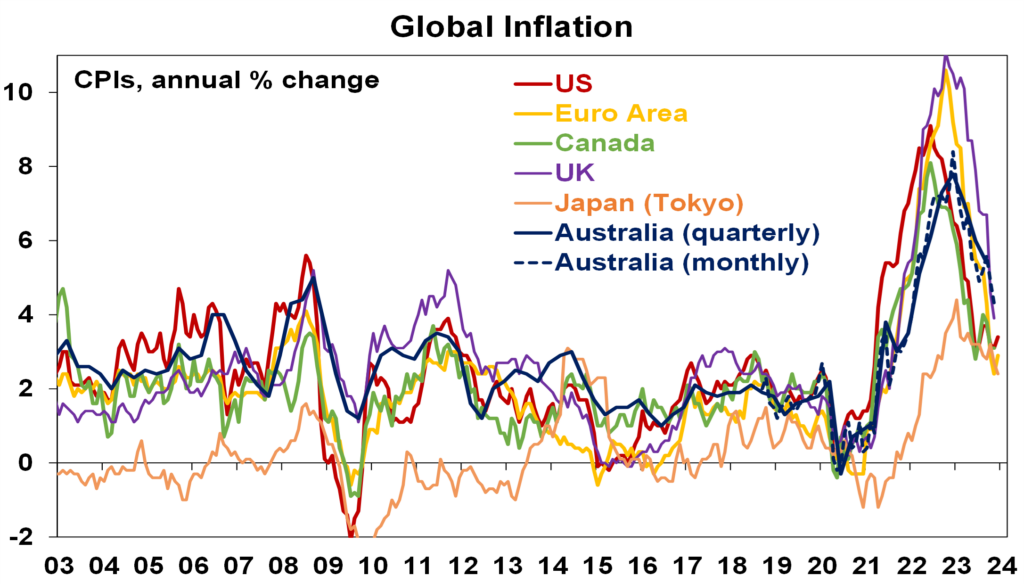

Inflation appears to be falling almost as quickly as it went up. In major developed countries it peaked around 8% to 11% in 2022 and has since fallen to around 3% to 4%. It’s also fallen in emerging countries.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

What’s driving the fall in inflation?

The rise in inflation got underway in 2021 and reflected a combination of massive monetary and fiscal stimulus that was pumped into economies to protect them through the pandemic lockdowns that was unleashed as spending (first on goods then services) at a time when supply chains were still disrupted. So it was a classic case of too much money (or demand) chasing too few goods and services. Its reversal since 2022 reflects the reversal of policy stimulus as pandemic support measures ended, pent up or excess savings has been run down by key spending groups, monetary policy has gone from easy to tight and supply chain pressures have eased. In particular, global money supply growth which surged in the pandemic has now collapsed.

Why is Australian inflation higher than other countries?

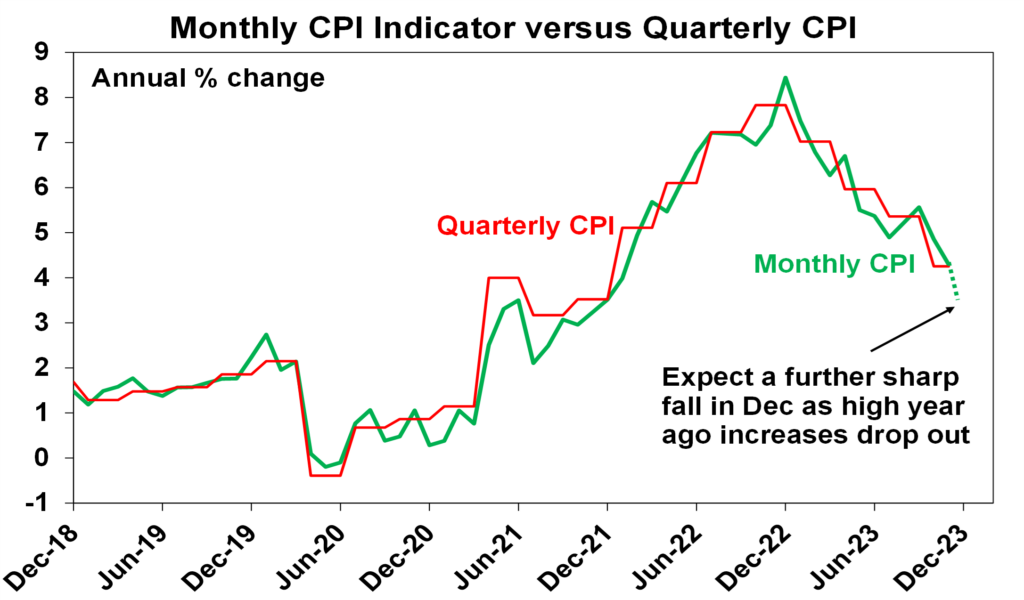

While there has been some angst about Australian inflation (at 4.3% year on year in November) being higher than that in the US (3.4%), Canada (3.1%), UK (3.9%) and Europe (2.9%), this mainly reflects the fact that it lagged on the way up and lagged by around 3 to 6 months at the top. The lag partly reflects the slower reopening from the pandemic in Australia and the slower pass through of higher electricity prices. So we saw inflation peak in December 2022, whereas the US, for instance, peaked in June 2022. But just as it lagged on the way up it’s still following other countries down with roughly the same lag. In fact, with a very high 1.5% month on month implied rise in the Monthly CPI Indicator to drop out from December last year, monthly CPI inflation is likely to have dropped to around 3.3% to 3.7% year on year in December last year, which is more in line with other countries.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

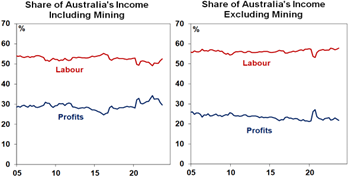

What about profit gouging?

There has been some concern that the surge in prices is due to “price gouging” with “billion dollar profits” cited as evidence. In fact, the Australian Government has set up an inquiry into supermarket pricing. There are several points to note in relation to this. First, it’s perfectly normal for any business to respond to an increase in demand relative to supply by raising prices. Even workers do this (e.g. asking for a pay rise and leaving if they don’t get one when they are getting lots of calls from headhunters). It’s the way the price mechanism works in allocating scarce resources. Second, national accounts data don’t show any underlying surge in the profit share of national income, outside of the mining sector. Finally, blaming either business or labour (with wages growth picking up) risks focusing on the symptoms of high inflation not the fundamental cause, which was the pandemic driven policy stimulus and supply disruption. This is not to say that corporate competition can’t be improved.

Source: ABS, RBA, AMP

What is the outlook for inflation?

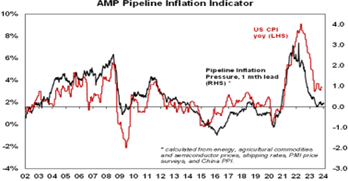

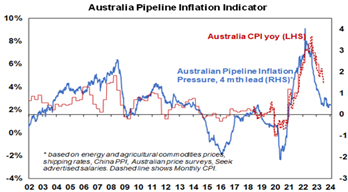

Our US and Australian Pipeline Inflation Indicators continue to point to a further fall in inflation ahead.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

This is consistent with easing supply pressures, lower commodity prices and slowing demand. It’s not assuming recession, but it is a high risk and if that occurred it would likely result in inflation falling below central bank targets. Out of interest, the six month annualised rate of core private final consumption inflation in the US, which is what the Fed targets, has fallen below its 2% inflation target. In Australia, it’s expected that the quarterly CPI inflation to have fallen to around 3% year on year by year end. The return to the top of the 2% to 3% target is expected to come around one year ahead of the RBA’s latest forecasts.

What are the risks?

Of course, the decline in inflation is likely to be bumpy and some say that the “last mile” of returning it to target might be the hardest. There are five key risks to keep an eye on in terms of inflation:

- First, the escalating conflict in the Middle East has the potential to result in inflationary pressures. Disruption to Red Sea/Suez Canal shipping is already adding to container shipping rates due to extra time in travelling around Africa. So far this has seen only a partial reversal of the improvement in shipping costs seen since 2022 and commodity prices and the oil price remain down. The US and its allies are likely to secure the route relatively quickly such that any inflation boost is short lived. The real risk though, is if Iran is drawn directly into the conflict, threatening global oil supplies.

- Economic activity could surprise on the upside again keeping labour markets tight, fuelling prices and wages, and hence sticky services inflation.

- Central banks could ease before inflation has well and truly come under control in a re-run of the stop/go monetary policy of the 1970s.

- In Australia, recent flooding could boost food prices and delays associated with industrial disputes at ports could add to goods prices. At present though, the floods are not on the scale of those seen in 2022 and it’s expected that any impact from both to be modest (at say 0.2%).

- Finally, and also in Australia if productivity remains depressed, 4% wages growth won’t be consistent with the 2% to 3% inflation target.

What lower inflation means for investors?

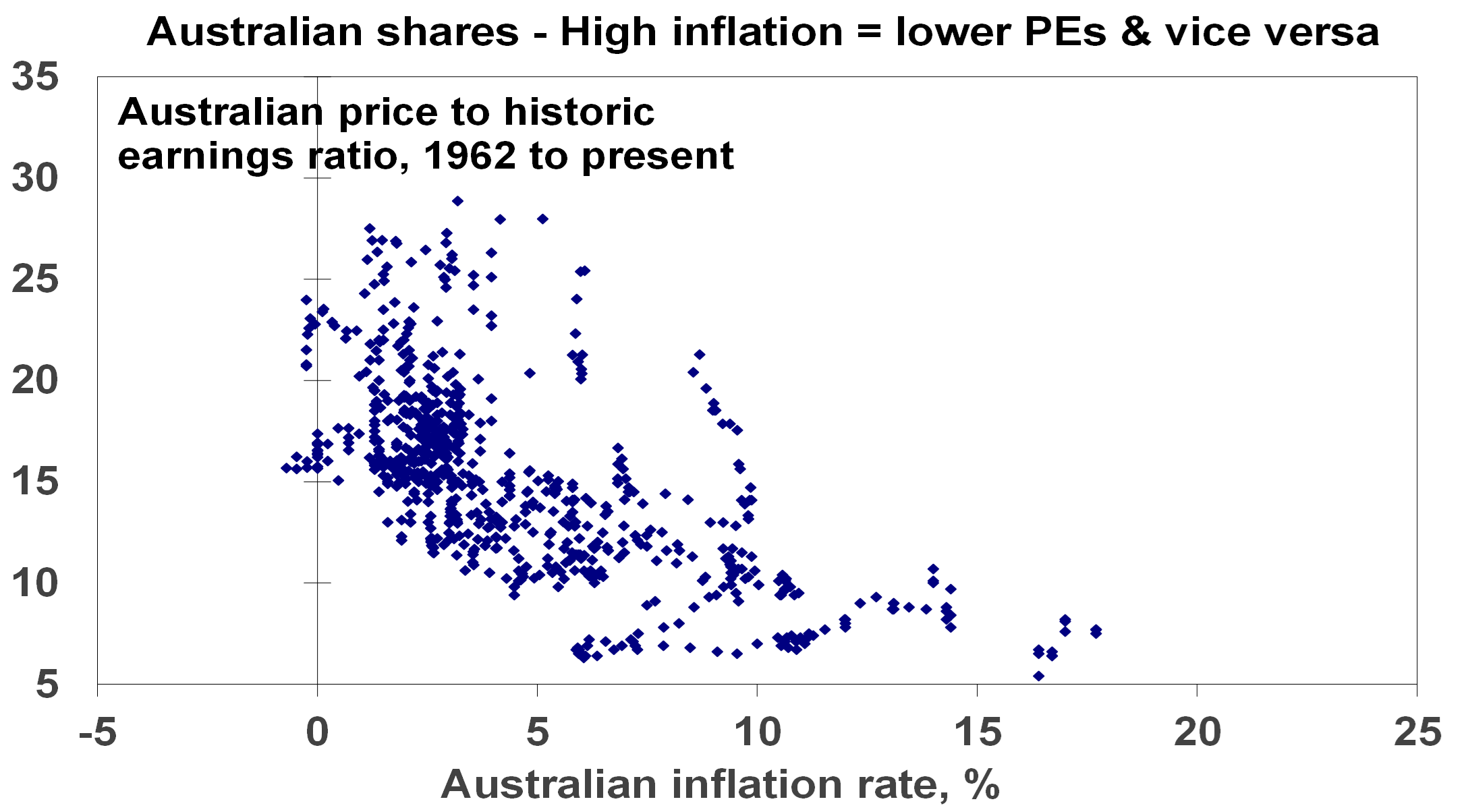

High inflation tends to be bad for investment markets because it means higher interest rates; higher economic uncertainty; and for shares, a reduced quality of earnings. All of which means that shares tend to trade on lower price to earnings multiples when inflation is high, and growth assets trade on higher income yields. We saw this in 2022 with bond yields surging, share markets falling and other growth assets pressured.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

So, with inflation falling, much of this goes in reverse as we started to see in the last few months. In particular:

- Interest rates will start to come down. The Fed is expected to start cutting in May and the European Central Bank (ECB) to start cutting around April, both with 5 cuts this year. There is some chance that both could start cutting in March. The RBA is expected to start cutting around June, with 3 cuts this year.

- Shares can potentially trade on higher price-to-earnings (PEs) than otherwise.

- Lower interest rates with a lag are likely to provide some support for real assets like property.

Of course, the main risk is if economies slide into recession, which will mean another leg down in share markets before they start to benefit from lower interest rates. This is not our base case but it’s a high risk.

Concluding comment

Finally, while inflation is on the mend cyclically, it’s worth remembering that from a longer term perspective we have likely now entered a more inflation prone world than the one prior to the pandemic, reflecting bigger government; the reversal of globalisation; increasing defence spending; decarbonisation; less workers and more consumers as populations age. So short of a very deep recession, don’t expect interest rates to go back to anywhere near zero anytime soon.

Source: AMP