Five lessons learned in 2023

1. Interest rate cycles can be different

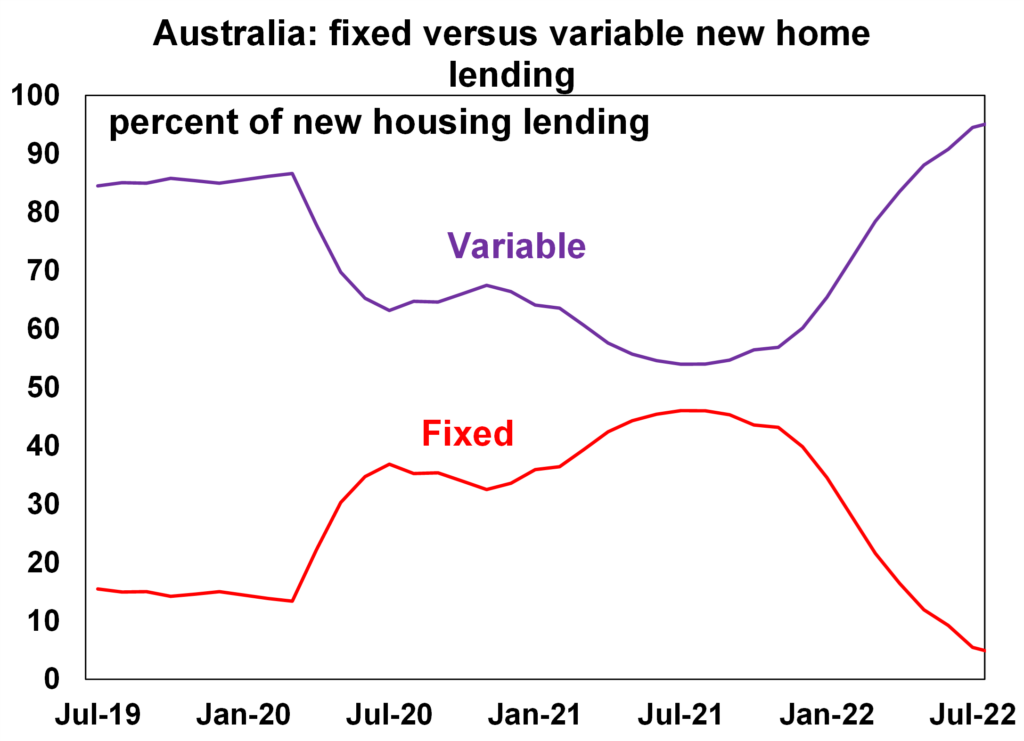

Students of economics are taught that monetary policy works with long and variable lags, up to 12-18 months. We had assumed that in the current cycle, the economy in 2023 would have been more negatively impacted from the rate hikes which began in May 2022. However, in the current cycle, rate hikes have taken longer than usual to impact the economy. This is elongating the monetary policy tightening cycle. One of the main reasons for this is that we have had a record number of households fixing their mortgage rates in recent years at ultra-low interest rates and a large chunk of households are still rolling off these fixed rates, providing a cushion to rising interest rates. After fixed rates bottomed at around 2.0% in early 2021, fixed rate lending reached a peak of around 46% of total new housing lending (see the chart below), well above its pre-COVID normal of 10-15%. With most fixed rate loans held for 3 years or less, these loans are now rolling off onto variable interest rates that around 3 times higher than the prior fixed rate loan. On the RBA’s estimates, by the end of this year, we will be around 60% of the way through the fixed to variable rate roll off. So, the impact of rising interest rates will still be impacting indebted households in 2024.

Source: ABS, AMP

The pass through of rate hikes to variable mortgage rates has also been lower than usual because of the heightened competition between lenders. As at September (when we have the latest data), the cash rate had risen by 4.0% but the pass through to variable interest rates was 3.3%. Usually, the pass through of rate changes to variable interest rates is closer.

2. Consumer incomes are not the only source of support for spending

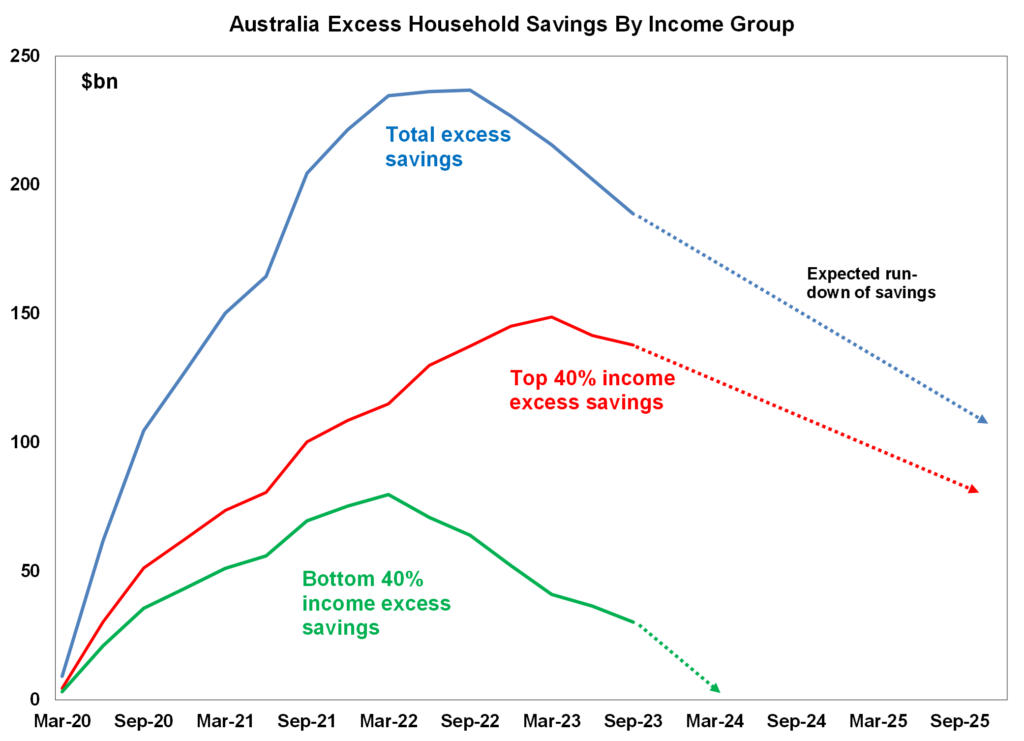

Australian consumers have managed to weather rate hikes better than we expected. While retail spending slowed over 2023 and retail volumes were negative from December 2022 – August 2023, spending on services for personal care, recreation and holiday travel has remained solid. Fixed rate lending has helped consumers weather interest rate hikes but we also underestimated the impact from high accumulated savings. At their peak, consumer accumulated savings reached $237bn in September 2022 and have been run down to $187bn as at September 2023. While this still seems high, these savings are not evenly distributed. On our estimates, the bottom 40% of household groups (the groups most impacted by high interest rates and elevated inflation) are likely to have used up their additional savings by early 2024. In contrast, high income earners (who are in a better position to absorb higher interest rates) still appear to have very high levels of savings (see the chart below). Similar differences are also observed across different age groups, with older households (who are likely to have less debt) holding the bulk of accumulated savings. Some of these older groups or higher income earners may never run down their pre-pandemic savings.

Source: ABS, AMP

So, it appears that excess savings will be less of a support to consumers (especially for those with a mortgage) in 2024 compared to this year. The expected weakening in the labour market in 2024 (based on the slowing in leading indicators of employment growth like job ads) also means that consumer incomes will be under more pressure, leading additional consumers to exhaust any additional savings. On the RBA’s own estimates, 13% of variable rate households were already in a negative cash flow position in July (with mortgage and essential repayments outpacing income). And for fixed rate mortgage holders, around 18% of households will be in a negative cash flow position when they roll off their fixed rate. These estimates were done before the November 0.25% rate hike so would look even higher now.

3. Soft and hard data can tell different stories

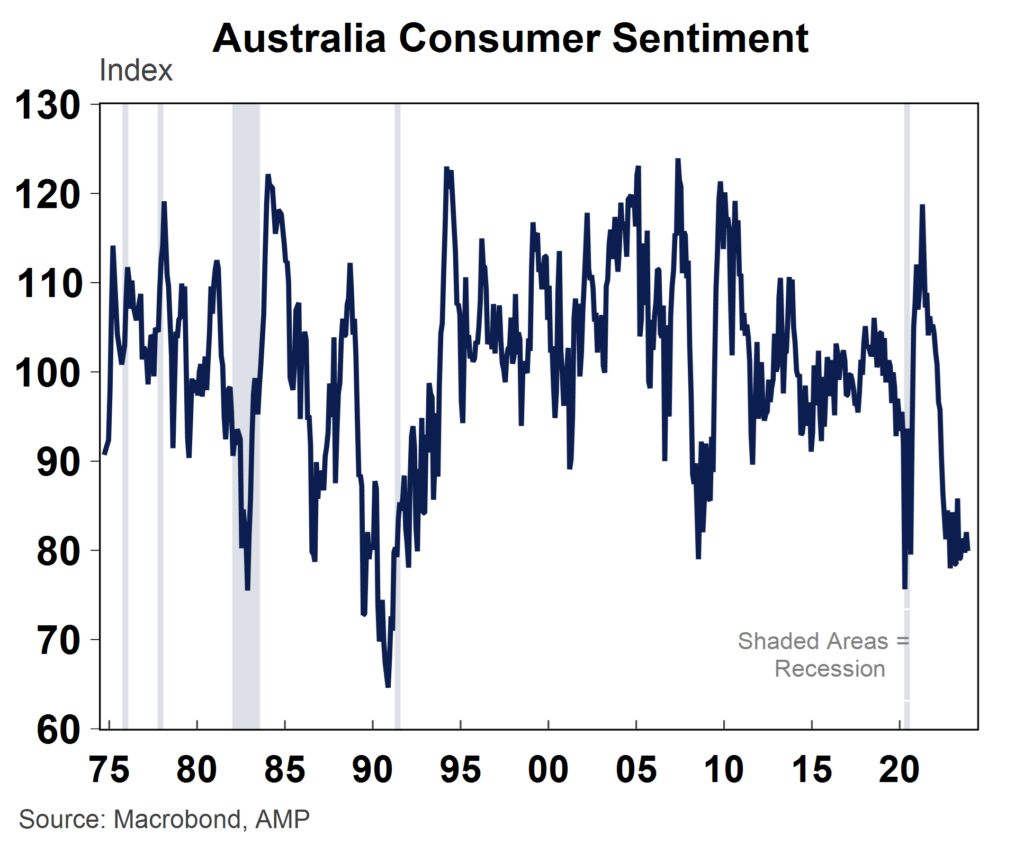

“Soft” data usually refers to surveys while “hard” data are the real economic activity indicators. According to the surveys, consumer sentiment has been very poor in 2023, and remains around recessionary-like levels (see the chart below).

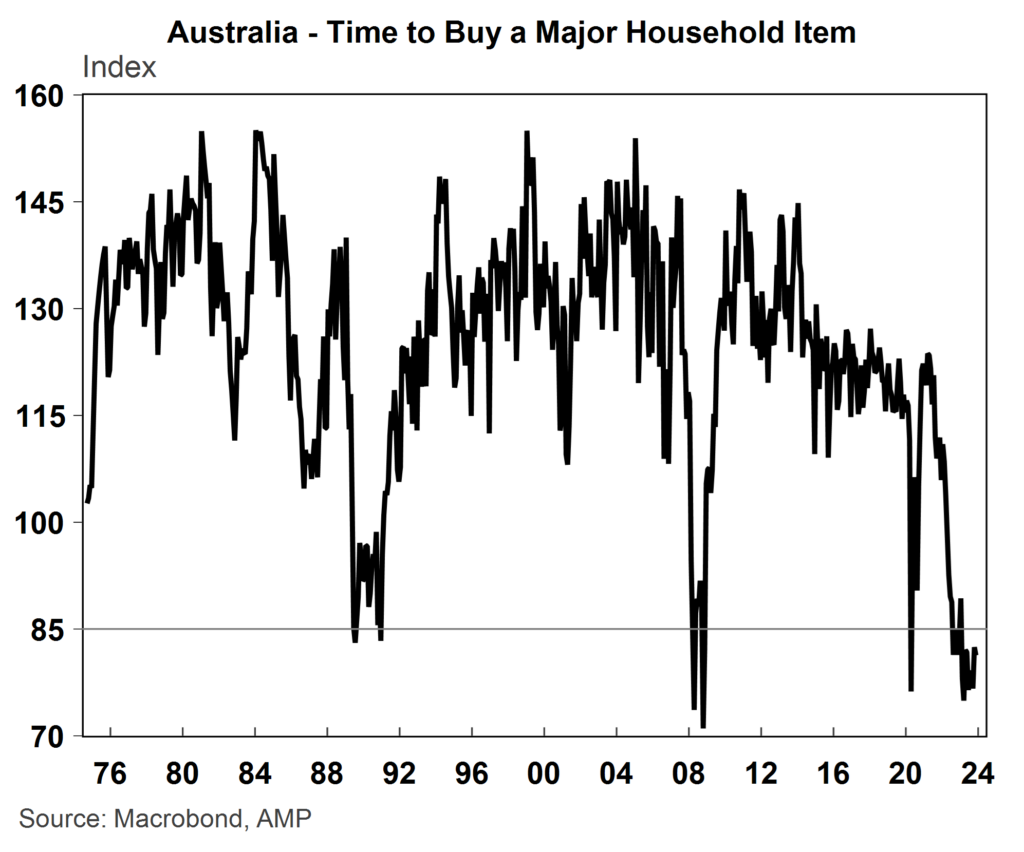

And consumers continue to indicate that it is not a good time to buy a household item (see the chart below), around its lowest levels on record.

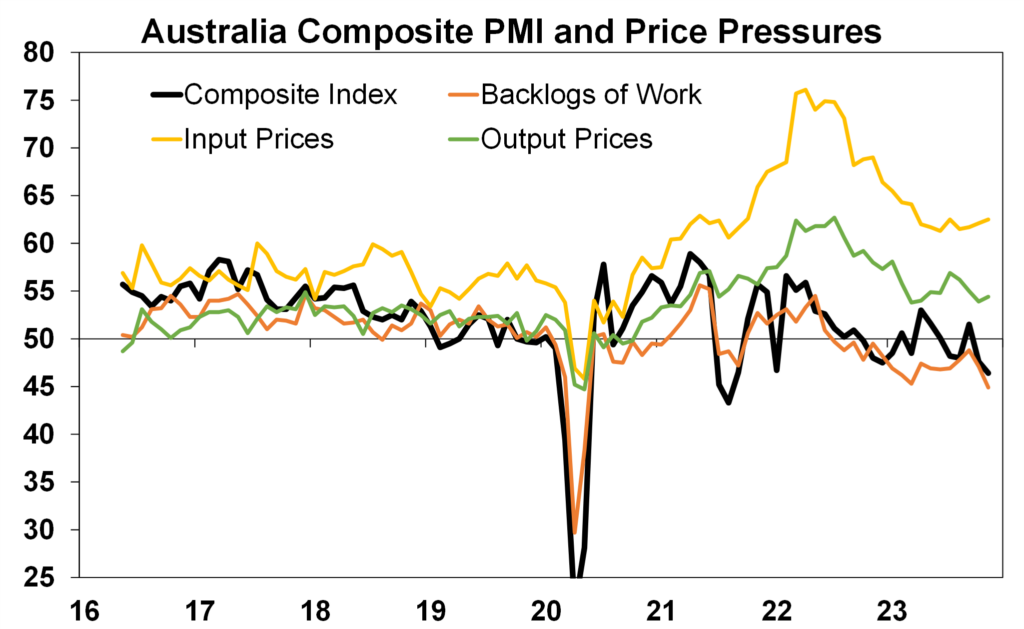

Similarly, the Australian PMI survey which is a gauge of national activity has been weak through most of 2023. An index level of 50 means that activity is neutral and the PMI has been averaging below 50 this year, indicating that activity is contracting (see the chart below).

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

We had put some weight to these indicators and expected the signals from them to show up in the “hard” data of actual economic activity. However, spending outcomes have been much stronger than the surveys would imply. While this could indicate that indicators from surveys are not always converted into actual outcomes, sometimes the hard and soft data end up catching up to each other. We find it likelier that the real activity indicators will slow in 2024, rather than the survey data weakening even further from here.

4. Government policies are important

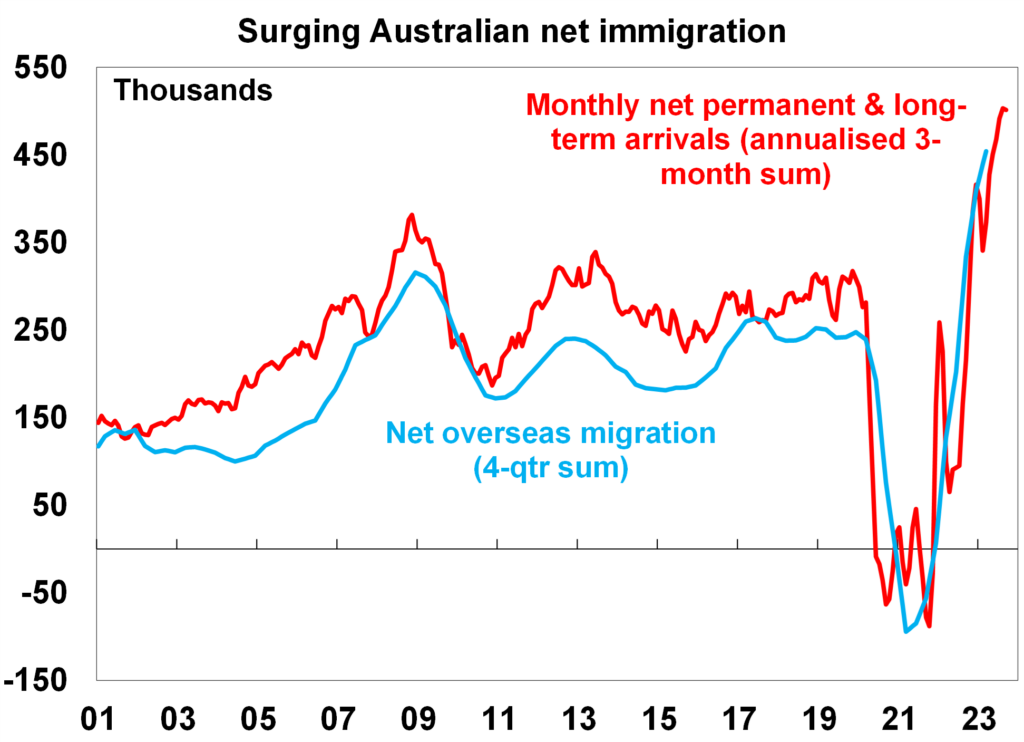

A catch up in Australian immigration after the COVID-19 pandemic was always likely but the extent of the increase in international arrivals has taken most commentators by surprise and we have written about it here. Annual overseas migration is running at over 500K/year (see the chart below) driven in particular by a rise temporary visas for skilled work and student visas. The surge in population has added to supply issues in the housing market, adding to rental growth and inflation. Largely as a result of higher immigration, we underestimated the extent to which home prices would rise in 2023 and thought inflation would start to slow at a faster pace in Australia. However, it does look like we have reached peak levels of immigration, with a softer pace likely in 2024.

Source: ABS, AMP

The past year has also shown that government policies also matter for the RBA. The government review on the RBA is resulting in multiple changes to the way the Board operates, including fewer but longer Board meetings and more involvement from Board members with the RBA and the public. This could have implications for how monetary policy decisions are made in 2024, if the Board members from the RBA (the Governor and Deputy Governor) end up having their views diluted from external board members.

5. Geopolitics matter but often have a different impact to what you initially expected

Major geopolitical events have been occurring frequently in recent years, impacting economies and markets. In 2023, concern about the US fiscal situation was one driver behind a lift in bond yields, although this proved temporary as yields have drifted back down again towards late 2023. The conflict in Israel recently has had major humanitarian impacts but the impact on financial markets has been more muted, despite fears that it would have a more negative impact on sharemarkets. The timing of specific events is very hard to predict. However, it is good to have a gauge about the broad risk events on the horizon. Politics will be important in 2024, as there are multiple elections including the US, Taiwan, Russia, India and European Parliamentary elections (around 45% of the global population will have an election in 2024), so investors need to bear in mind the volatility associated with geopolitics on their portfolios.

Source: AMP