There remain five reasons to expect the $A to rise

Back in November we saw five reasons to expect a higher $A. These largely remain valid and the $A seems to be perking up again.

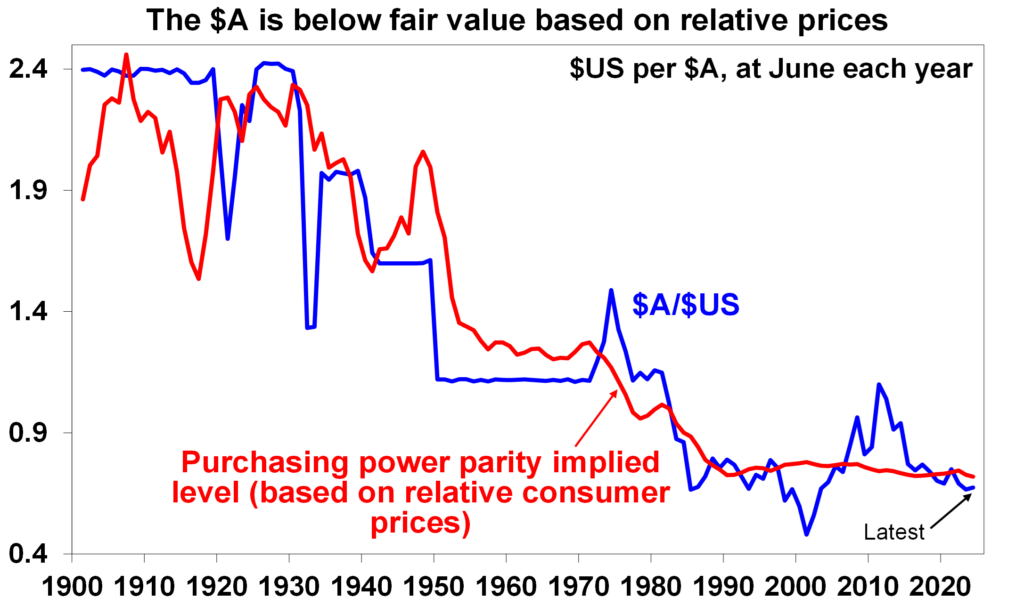

- Firstly, from a long-term perspective the $A remains somewhat cheap. The best guide to this is what is called Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) according to which exchange rates should equalise the price of a basket of goods and services across countries – see the red line in the first chart. If over time Australian prices and costs rise relative to the US, then the value of the $A should fall to maintain its real purchasing power. And vice versa if Australian inflation falls relative to the US. Consistent with this, the $A tends to move in line with relative price differentials or its PPP implied level over the long-term. This concept has been popularised over many years by the Big Mac Index in The Economist magazine. Over the last 25 years the $A has swung from being very cheap (with Australia being seen as an old economy in the tech boom) to being very expensive into the early 2010s with the commodity boom. Right now, it’s modestly cheap again at just above $US0.67 compared to fair value around $US0.72 on a PPP basis.

Source: RBA, ABS, AMP

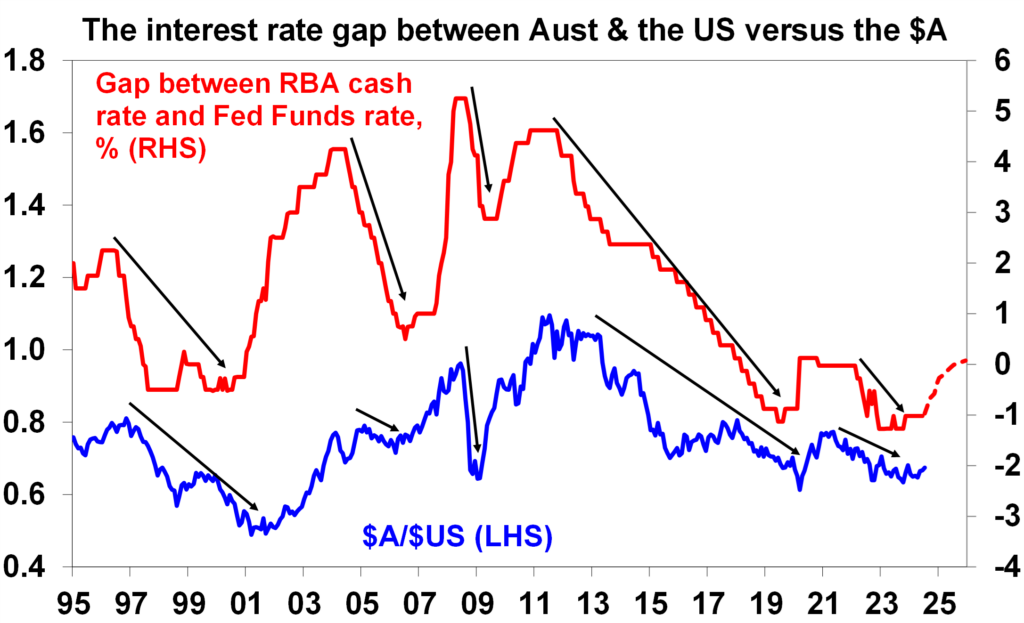

- Second, after much angst not helped by another US inflation scare, relative interest rates might be starting to swing in Australia’s favour with increasing signs that the Fed is set to start cutting rates from September whereas there is still a high risk that the RBA will hike rates further. Central banks in Switzerland, Sweden, Canada and the European Central Bank have already started to cut rates. Money market expectations show a narrowing of the negative gap between the RBAs cash rate and the Fed Funds rate as the Fed is expected to cut by more than the RBA. As can be seen in the next chart, periods when the gap between the RBA cash rate and the Fed Funds rate falls have seen a fall in the value of the $A (see arrows – and this being the case more recently) whereas periods where the gap is widening have tended to be associated with a rising $A. More broadly the $US is expected to fall further against major currencies as US interest rates top out.

The dashed part of the rate gap line reflects money mkt expectations. Source: Bloomberg, AMP

- Third, global sentiment towards the $A remains somewhat negative and this is reflected in short or underweight positions. In other words, many of those who want to sell the $A may have already done so and this leaves it susceptible to a further rally if there is any good news.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

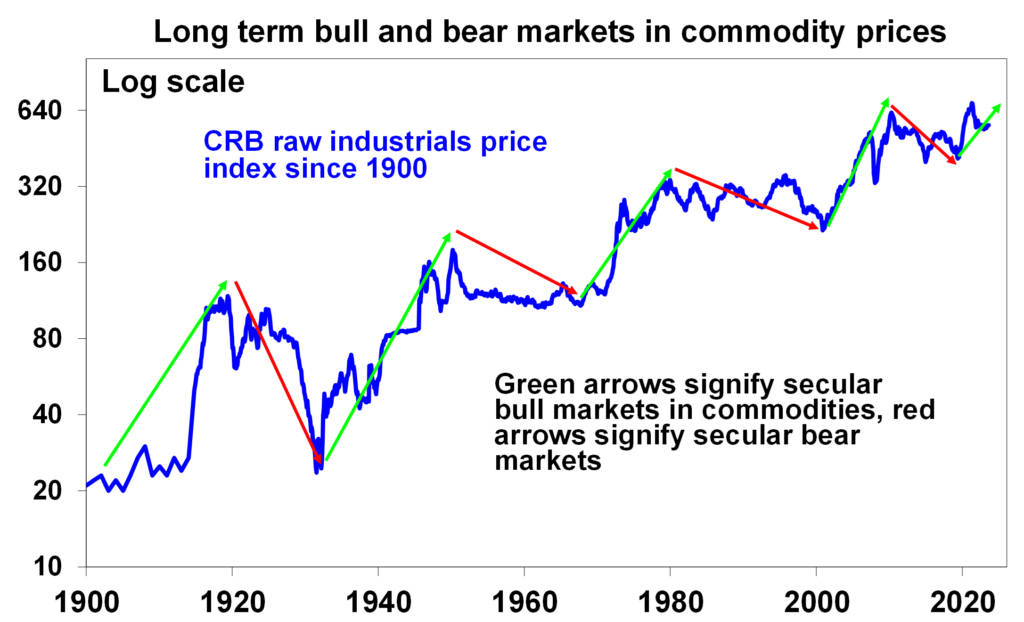

- Fourth, commodity prices look to be embarking on a new super cycle. The key drivers are the trend to onshoring, reflecting a desire to avoid a rerun of pandemic supply disruptions and increased nationalism, the demand for clean energy and vehicles and increasing global defence spending, all of which require new metal intensive investment compounded by global underinvestment in new commodity supply. This is positive for Australia’s industrial commodity exports.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

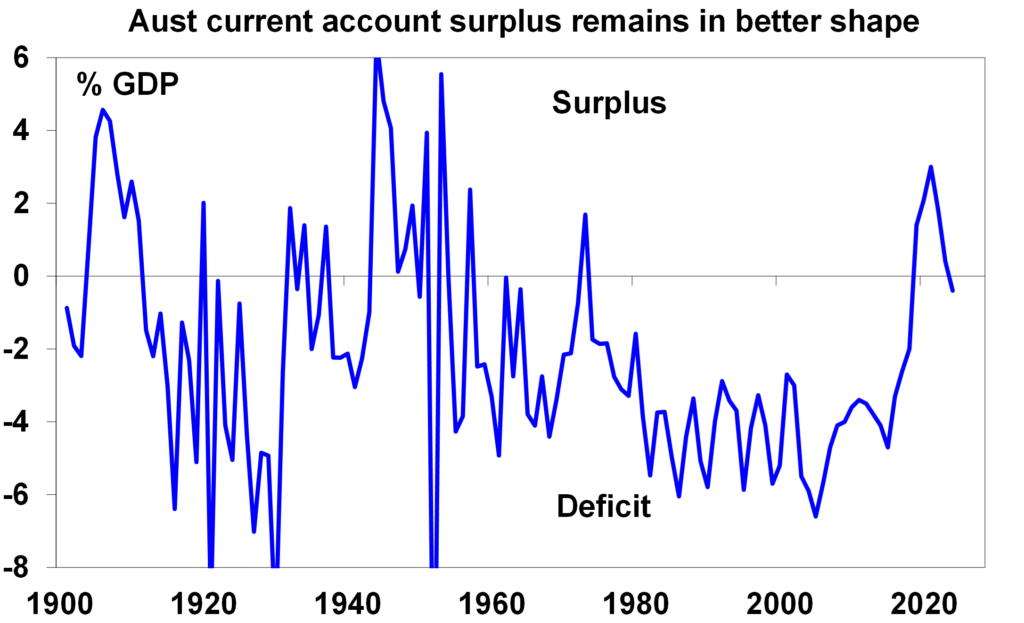

- Finally, Australia’s current account surplus has slipped back into a small deficit as commodity prices have cooled and services imports have risen (particularly, Australians travelling overseas) but it remains much better than it used to be over the decades prior to the pandemic. A current account around balance means roughly balanced natural transactional demand for and supply of the $A. This is a far stronger position than pre-COVID when there was an excess of supply over demand for the $A which periodically pushed the $A down.

Source: ABS, AMP

Where to from here?

We expect the combination of the Fed cutting earlier and more aggressively than the RBA, a falling $US at a time when the $A is undervalued and positioning towards it is still short, to push the $A up to around or slightly above $US0.70 into next year.

Recession and a new Trump trade war are the main risks

There are two main downside risks for the $A. The first is if the global and/or Australian economies slide into recession – this is not our base case but it’s a very high risk. The second big risk would be if Trump is elected and sets off a new global trade war with his campaign plans for 10% tariffs on all imports and a 60% tariff on imports from China. If either or both of these occur, it could result in a new leg down in the $A, as it is a growth sensitive currency, and a rebound in the relatively defensive $US.

What would a rise in the $A mean for investors?

For Australian-based investors, a rise in the $A will reduce the value of international assets (and hence their return), and vice versa for a fall in the $A. The decline in the $A over the last three years has enhanced the returns from global shares in Australian dollar terms. When investing in international assets, an Australian investor has the choice of being hedged (which removes this currency impact) or unhedged (which leaves the investor exposed to $A changes). Given our expectation for the $A to rise further into next year there is a case for investors to stay tilted towards a more hedged exposure of their international investments.

However, this should not be taken to an extreme. First, currency forecasting is hard to get right. And with recession and geopolitical risk remaining high, the rebound in the $A could turn out to be short lived. Second, having foreign currency in an investor’s portfolio via unhedged foreign investments is a good diversifier if the economic and commodity outlook turns sour, as over the last few decades major falls in global shares have tended to see sharp falls in the $A which offsets the fall in global share values for Australian investors. So having an exposure to foreign exchange provides good protection against threats to the global outlook.

Source: AMP